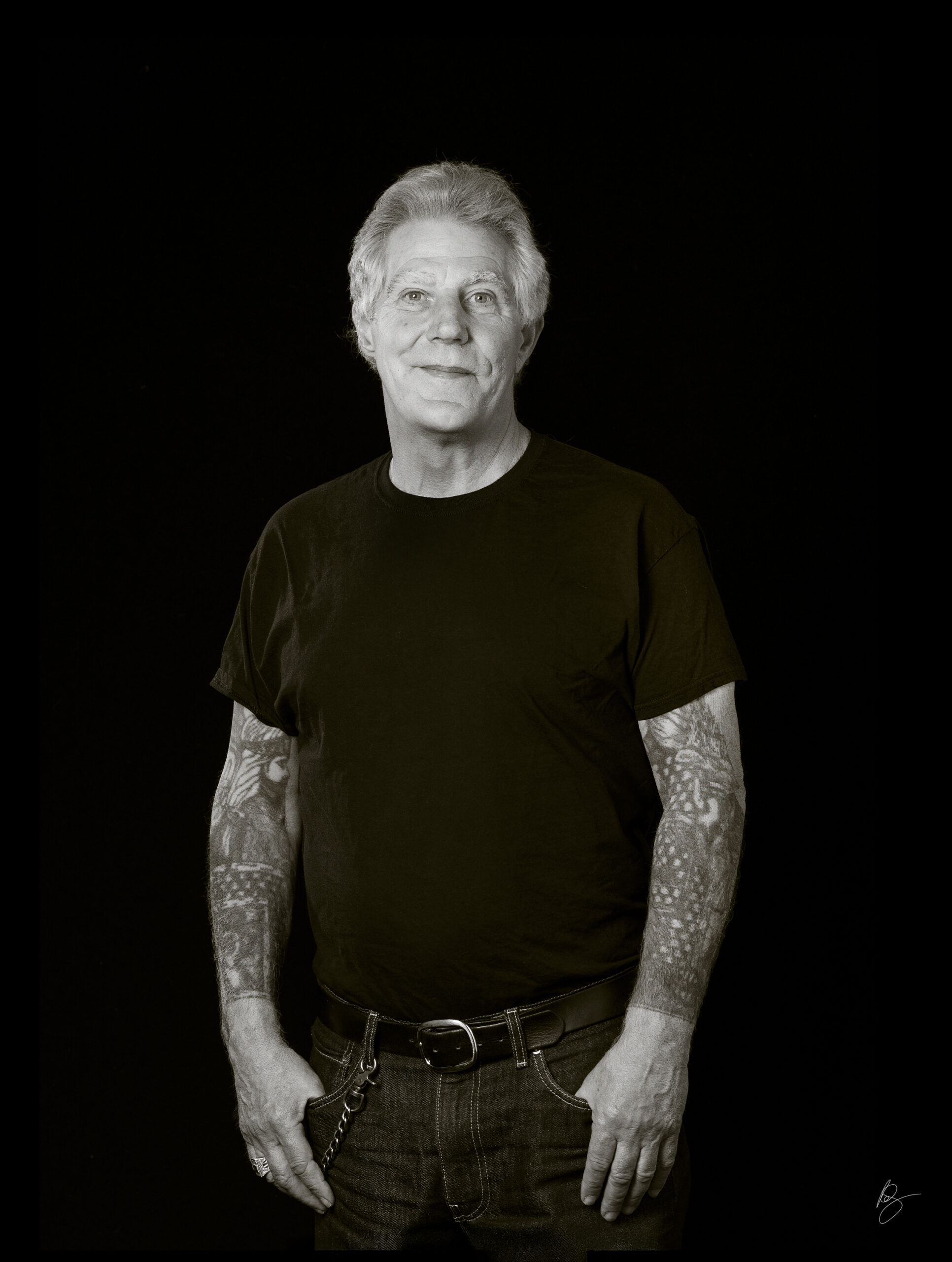

At a Glance

- Innocent Years Served: 40 Years

- Sentence: Life without the Possibility of Parole

- Wrongful Conviction: First Degree Aggravated Murder & Rape in the First Degree

- Year: 1982

- Jurisdiction: Snohomish County

- Released: October 2021

- Exonerated:

- Cost of Wrongful Incarceration*: $2,545,040

- Lost Wages**: $2,334,592